Lenôtre's Description of the Conciergerie, and Conditions Within, During the French Revolution (and a POW P.S.)

The mammoth, looming Conciergerie as seen when one walks along the Seine.

Let's talk about the Conciergerie.... as it was, as it is...

The prison was altered after the Revolution and, who knows, maybe after Lenôtre wrote his descriptions in Paris in the Revolution which was over a hundred years ago. It's possible that the rooms displayed, and their identification, have changed somewhat over the years. If anyone would like to illuminate the way and correct me, I'd completely welcome their input. I'd love to know exactly what went on where.

What's in all of those rooms?! The section I've been in covers less than a 1/2" square of the complex.

Transferring Prisoners to the Conciergerie, by Armand de Polignac, 1804

The arched entrance, through which prisoners came and went, is still in place, though there's no wall separating the arch from the stairs leading to the entry of the Palais de Justice. Note the steeple-topped Sainte Chapelle to the left of the courthouse.

The Cour du Mais (courtyard) as seen today, without the wall shown in Armand de Polignac's painting. The building has seen changes, particularly those that occurred as a result of an overhaul during the Haussmann era, but the arched doorway at which the tumbrels delivered and picked up prisoners is intact and located on the far right side of the main hall of the building.

Closer view of arched entrance

The Arrival and Processing of Prisoners

G. Lenôtre's (a pseudonym) description of what a typical Citoyen experienced on the date of his arrest:

"When a suspect was arrested at his house, it was generally in a hackney-coach that the agents of the Committees conveyed him to the prison of the Palace of Justice. The vehicle entered the Cour du Mai and came to a stop a few paces from the gate which shut in the little back-court of the Conciergerie. The grand perron of the Palace was almost always, particularly in the afternoon, when the carts came to fetch the daily rations of the guillotine, occupied by a crowd of women, who appeared to be seated in an amphitheatre awaiting a favorite play.

When the prisoner alighted from the hackney-coach, the whole amphitheatre rose as one woman and gave vent to a prolonged shout of joy. Clapping of hands, stamping of feet, convulsions of laughter, expressed the ferocious delight of these furies at the arrival of a new prey. The short distance which the unfortunate man had to traverse on foot was still long enough for him to receive in the face the filth which rained on him from every side, and which, thrown from the top of the perron, pursued him so far as the narrow courtyard, which was always thronged with soldiers, gaolers, executioner's assistants, spies of the Committees, suppliants, petitioners, or privileged spectators."

So, basically, the poissardes, the "fishwives" of Paris, welcomed the prisoners with mocking cheers and trash.

"All the victims of the Revolutionary scaffold have passed through the narrow door which gave access to it;" Lenôtre wrote of this door, "their feet have trod the flagstones which still pave it today. So soon as they entered, they found on the left a door through which they passed into the registrar's office... It was in the registrar's office that newcomers were received and their names entered in the registers; it was there that the gaol-entires were collected and that the executioner came to give a receipt for the condemned persons who were delivered to him."

Lenôtre states that the room used to be partitioned and that the back section is where the condemned waited, on a wooden bench, to be picked up by the executioner.

Comte Beugnot, one of the rare inhabitants of the Conciergerie that lived to tell about it, left this account: "The day when I entered, two men were awaiting the arrival of the executioner. They had been deprived of their clothes, and already had their hair disheveled and the necks prepared. Whether intentionally or not, they kept their hands in the position in which they were going to be bound, and endeavored to assume proud and disdainful attitudes. Mattresses stretched on the floor showed that they had passed the night there, and that they had already suffered the long anguish which that must have entailed. One saw near them the remains of the last meal of which they had partaken. Their clothes were thrown here and there, and two candles, which they had neglected to extinguish, repulsed the day in order to illuminate this scene only by a funereal light."

Lenôtre states that the room used to be partitioned and that the back section is where the condemned waited, on a wooden bench, to be picked up by the executioner.

Comte Beugnot, one of the rare inhabitants of the Conciergerie that lived to tell about it, left this account: "The day when I entered, two men were awaiting the arrival of the executioner. They had been deprived of their clothes, and already had their hair disheveled and the necks prepared. Whether intentionally or not, they kept their hands in the position in which they were going to be bound, and endeavored to assume proud and disdainful attitudes. Mattresses stretched on the floor showed that they had passed the night there, and that they had already suffered the long anguish which that must have entailed. One saw near them the remains of the last meal of which they had partaken. Their clothes were thrown here and there, and two candles, which they had neglected to extinguish, repulsed the day in order to illuminate this scene only by a funereal light."

The next time I go, I'm going to ask questions.

I want to know what's written in this book and if it's original, don't you?!

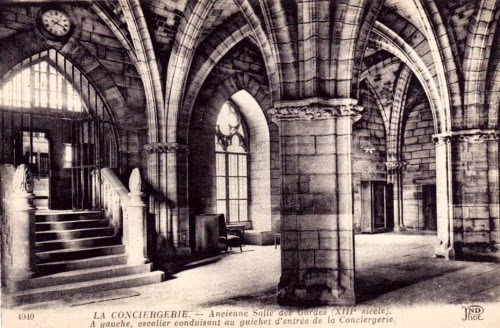

the Guard Room

scissors at the ready for the final haircut

Because it was the center of administrative activities such as admitting and discharging prisoners, cutting hair in preparation for the blade, and so forth, and because of its proximity to the Women's Courtyard, this area was teeming with people at all hours of the day and night. And, noisy. In the face of death, groups of men emboldened themselves by singing, in chorus, at the tops of their voices, guard dogs barked, women chattered, guards barked orders and questioned prisoners and visitors.

The Women's Courtyard: "A flower-bed, studded with flowers, but encircled with iron."

The Women's Courtyard was a well-used part of the prison and conveniently located to the other rooms pictured and described here.

Beugnot's memoir preserves a poignant scene for us to consider as he describes imprisoned women hanging on to the rituals of a society to which they no longer belonged, attempting to keep up the pretenses of their old lives. Referring to the daily scene in the Women's Courtyard, he writes:

"It was our favourite walk. We went down there so soon as we were let out of our dungeons. The women were allowed to go out at the same time, but they did not do so quickly as we did. Their toilette claimed its indefeasible rights. They appeared in the morning in a coquettish négligé, the parts of which were adjusted so neatly and gracefully that the general effect did not give the least indication that they had passed the night on a pallet, or more frequently, on fetid straw. As a general rule, the well-bred women that were brought to the Conciergerie preserved there until the end the sacred fire of good manners and good taste. When they had appeared in the morning in négligé, they went up to their rooms again and at midday we saw them come down dressed with care, and their hair becomingly arranged. Their manners were no longer those of the morning; they had something more distinguished and a kind of dignity about them. In the evening they appeared in deshabille. I observed that all the women who were able to do so remained faithful to the three costumes of the day. The other supplied the place by as much neatness and cleanliness as was possible in such a place. The Women's Court possessed a treasure - a fountain which provided them with water whenever they wanted it - and I used to watch every morning those poor unfortunate creatures who had only brought with them, or perhaps only possessed, one garment, occupied around this fountain, about which moved an excited crowd, washing, bleaching, and drying."

"The first hour of the day was consecrated by them to these cares, from which nothing would have distracted them, not even a writ of accusation, Richardson has observed that the care of clothes and the passion for making up parcels counter-balance, if they do not outweigh, in the mind of women the most important interests. I am persuaded that at this period no promenade in Paris presented a gathering of more elegantly dressed women than the court of the Conciergerie. It resembled a flower-bed studded with flowers, but encircled with iron."

The fountain basin, around which women gathered to wash their clothing and talk, is still in the Women's Courtyard.

This picture was taken from within the sectioned off area of the Women's Courtyard, known as the Corner of Twelve, close to the arched entrance through which prisoners entered and exited. It is on one's left when entering the prison and on the right when leaving. It was on the these cobblestones, through this gate, with this view, that the departing prisoners said good-bye to friends as they waited to be loaded into the cart. The wash basin is barely visible on the right, behind the open gate.

This is the view of the Women's Courtyard with the basin on the left and the Corner of Twelve straight ahead. The area inside the section of the building on the left holds the chapel built by Louis XVIII in honor of Marie Antoinette, the small cell represented as her cell, and the cell that is made up to look like her cell with her in it. Although the rooms have been altered and nothing is exactly as it was, she was actually kept in that general area. She lived in two different cells. One before the Carnation Affair and, for reasons of security, one after.

Living Conditions

a luxurious semi-private cell for the those that had money to pay for it

Changes to the Conciergerie include the clearing of three immense rooms that make up a principal portion of the area open to the public today. What is now a spectacular display of Gothic architecture was, during the Revolution, criss-crossed with partitions and wooden galleries built next to and on top of each other, described by Lenôtre as a "hive of cells... swarming with prisoners, rats, and vermin." There are a couple of vivid scenes of the Conciergerie in the 1983 movie Danton, starring Gerard Depardieu that depict the prison the way I imagine it to have been.

Consider this official reported filed by a prison inspector during the Revolution.:

"... What contributes to drive the prisoners to despair is the inhumanity with which they are crowded together in the same room, and the incalculable torments which they experience during the night. I visited them at the opening of the prison, and I know not language strong enough to describe the feeling of horror which I experienced on seeing in a single room twenty-six men collected, lying on twenty-one straw mattresses breathing the foulest air and covered with half-rotten rags; in another, forty-five men, huddled together on ten pallets; in a third, thirty-eight men in a dying state squeezed on to nine small beds; in a fourth, a very small room, fourteen men, of whom four could find no place on which to lie down; finally, in a fifth, sixth and seventh room eighty-five poor wretches hurting one another in order to be able to stretch themselves on sixteen straw mattresses full of vermin, and none of them being able to find anywhere to lay his head. Such a spectacle made me recoil with horror, and I shudder still while endeavoring to give some idea of it. The women were treated the same way; fifty-four are compelled between them to sleep on nineteen straw mattresses, or to take it in turns to remain standing, in order not to be stifled by lying one on top of another."

********************************************************

Personal note: I won't get into a futile attempt at comparing the Conciergerie of the Reign of Terror and the Hanoi Hilton/Alcatraz prison of the Vietnam War. Just by virtue of the fact that most prisoners of that Conciergerie must be considered worst.

But, the Hanoi Hilton and, especially its sub-prison, Alcatraz, were, quality of life-wise, worse, in my estimation. My father's experience there - almost eight years (four in solitary confinement), torture, tiny, dark cell was inconceivably horrendous. But, he did come home. For that, he was (and, we were) grateful.

For more on that story, read Defiant by Alvin Townley.

The Hanoi Hilton: Designed and built by the French...

Comments