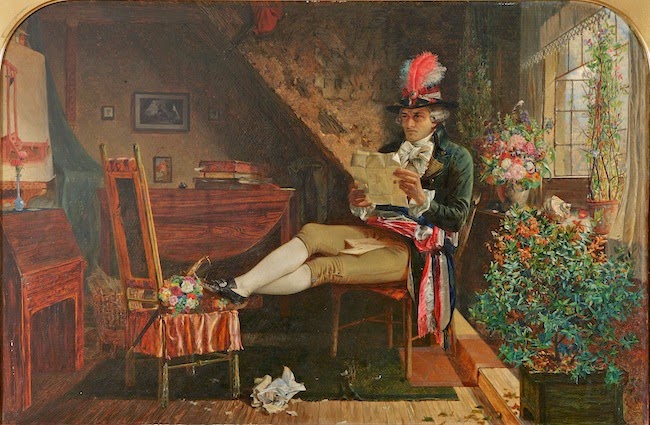

18th Century: Robespierre Receiving Letters from Friends of his Victims with Assassination Threats by William Henry Fisk

Like everything, there's more than one way to look at the painting. It's just one more thing for me to puzzle over and I can't seem to let the era go until I feel like I understand.

I have the sense that Robespierre wouldn't have wanted to read letters from the friends of his victims nor the farewell letters prisoners wrote before their executions. According to what I've read, he didn't attend executions. He sometimes fell ill and didn't attend especially stressful meetings and sessions. He seems to have hidden behind the vernacular (am I using that word correctly?) of Virtue in order not to face, head on, how far out of control events had spun. Maybe he didn't want to admit to himself what he was doing.

It's a fact that Marie Antoinette's last letter to her sister-in-law, Princesse Élisabeth, was found under Robespierre's mattress after his death. (Or so I've read. I didn't find it myself, so how can I be sure?) Did he not given it to someone, say, Fouquier-Tinville, who had a large collection of them, because he didn't want to face that the woman he'd been instrumental in destroying had been the sort of woman whose last words were, in my opinion, sublimely beautiful? Read Marie Antoinette's last letter and judge for yourself.

Many convicted prisoners wrote letters to their loved ones (and occasionally to their enemies, the creditors, or others) which, instead of being delivered to their intended recipients, were handed over to Prosecutor Fouquier-Tinville and ended up in the French National Archives. Eventually, someone came upon the boxes and published them at which time, at long last, the descendants of the victims of the guillotine were able to read their final missives.

To remember and honor these men and women, by allowing them to express themselves, more than two hundred years later, seems the least I can do...

So, here are a few...

Armand Louis de Gontaut, duc de Biron, (more commonly known to history as the duc de Lauzun, the title he held as a young man - those pesky title changes that make it hard to keep track of who's who), led the unit Lauzun's Legion during the American Revolution. He was well-liked, well-respected, and his romantic exploits were well-known. Count Axel Fersen, who also fought in the American Revolution, wrote to his father from America, referring warmly and admiringly of Lauzun. Their friendship must've cooled in the ensuing years when Lauzun took the principles of independence and applied them to his native country to the detriment of much of what Fersen held dear. He became critical of Marie Antoinette and the monarchy and commanded troops in the revolutionary French army.

The duc de Biron was denounced, in July 1793, with the broad, but nonetheless deadly, accusation of "lack of civic virtue" and was sentenced to death. Not surprisingly, aristocrats who switched allegiances and joined the People were often viewed with suspicion. At his trial, the Prosecutor, Fouquier-Tinville described him as having "abjured his king, his class, and his religion." It's curious that Fouquier-Tinville would find fault with that since it was a requirement of the Revolution. According to history, the duc de Biron, offered a glass of wine to the executioner, saying "You must need nerve in your business."

His last letter was to his aging father.:

"I am condemned. I shall die tomorrow in the sentiments of religion, of which my dear papa has set me the example, and which are worthy of him. My long agony derived much consolation from the certainty that my dear papa will not give way to grief of any kind... I have two Englishwomen who have been with me twenty years and who have been detained as prisoners since the decree on foreigners. I was their only resource. I commend them to the succour and extreme kindness of my dear papa, whom I love. I respect and embrace him for the last time with all my heart.

Biron

**************************************************************************

Madame Roland, the former Marie-Jeanne Philipon, Girondist, intellectual, patriot, writer, hostess of a salon attended by influential men of Paris during the Revolution. Died on the scaffold in November of 1793. Husband, Jean-Marie, Girondist, Minister of the Interior, a fugitive, killed himself when he learned of her execution. The man she considered the love of her life, another Girondist fugitive who along with Pétion of the Varennes debacle, committed suicide and was found partially eaten wolves,

Last letter to her twelve year old daughter, Eudora, from prison:

I do not know, darling, whether I shall be allowed to see or write to thee again. Remember thy mother. These few words contain all the best that I can say to thee. Thou hast seen me happy in the discharge of my duties, and in being useful to those who suffer. This is the only way of being so. Thou has seen me placid in misfortune and captivity, because I had no remorse, but had the recollection and joy left by good actions. These are the only means of bearing the ills of life and the vicissitudes of fate. Perhaps, and I hope so, thou art not reserved for ordeals like mine, but there are others from which thou wilt nevertheless have to defend thyself. A serious and busy life is the first safeguard from all perils, and necessity as well as wisdom enforces thee to steady work. Be worthy of thy parents. They leave thee great examples, and if thou knowest how to profit by them thou wilt not lead a useless existence. Farewell, dear child thou whom I suckled, and whom I would fain imbue with all my sentiments. A time will come when thou wilt be able to appreciate all the effort that I am making at this moment not to be overcome by that sweet image, I clasp thee to my bosom. Farewell, my Eudora.

*************************************************************************

From Jean Baptisge Emanuel Rouettiers, aged 45, a former groom in waiting to Louis XVI to his wife, Citoyenne Rouettiers, Marais, Paris.

I approach the fatal end, my dear wife and children. I clasp you affectionately to my heart, which still beats and will beat to the last breath for you. Ever love one another, all three. Be happy with one another, and do not forget thy husband and father.

These sad words are sufficient representation. Amusing or upbeat good-bye letters are hard to come by. Non-existent, really, but there's a glint of wry humor in this one - intended or not.:

From Antoine Pierre Léon Dufrene to Citizen Fourdray, Commissary of Marine, Cherbourg.:

Receive, wretch, my eternal adieu. I do not know whether thou did it purposely. Although I know that thou art a scoundrel, I cannot bring myself to think thee so malicious. All that I can say to thee is that the letters which I had confided to thee have conducted me to the scaffold. If it was through malice, thy turn will soon come. Adieu.

In the letters to which Dufrene refers, he had written "It is impossible to say or write anything without risk of the guillotine. There would be many things to tell you of the present state of France, but I shall not venture on anything, and you will guess the reason. However nice the guillotine when you accommodate yourself to it, and whatever courage thus far shown by the heroes of this Revolutionary invention, I have no mind to try it." Try it, he did. It wasn't a try that was given a second.

Comments